The Republican Ghost of the Conservative Party of Canada

How a little-known Republican consultant rewired the Canadian right — and why his methods still haunt the party today.

Prologue: Once you see the wiring, you can’t unsee it

If you’ve ever wondered why today’s Conservative Party of Canada feels less like the old Progressive Conservatives and more like a message-disciplined political machine, there’s a reason.

It isn’t only generational change or social media.

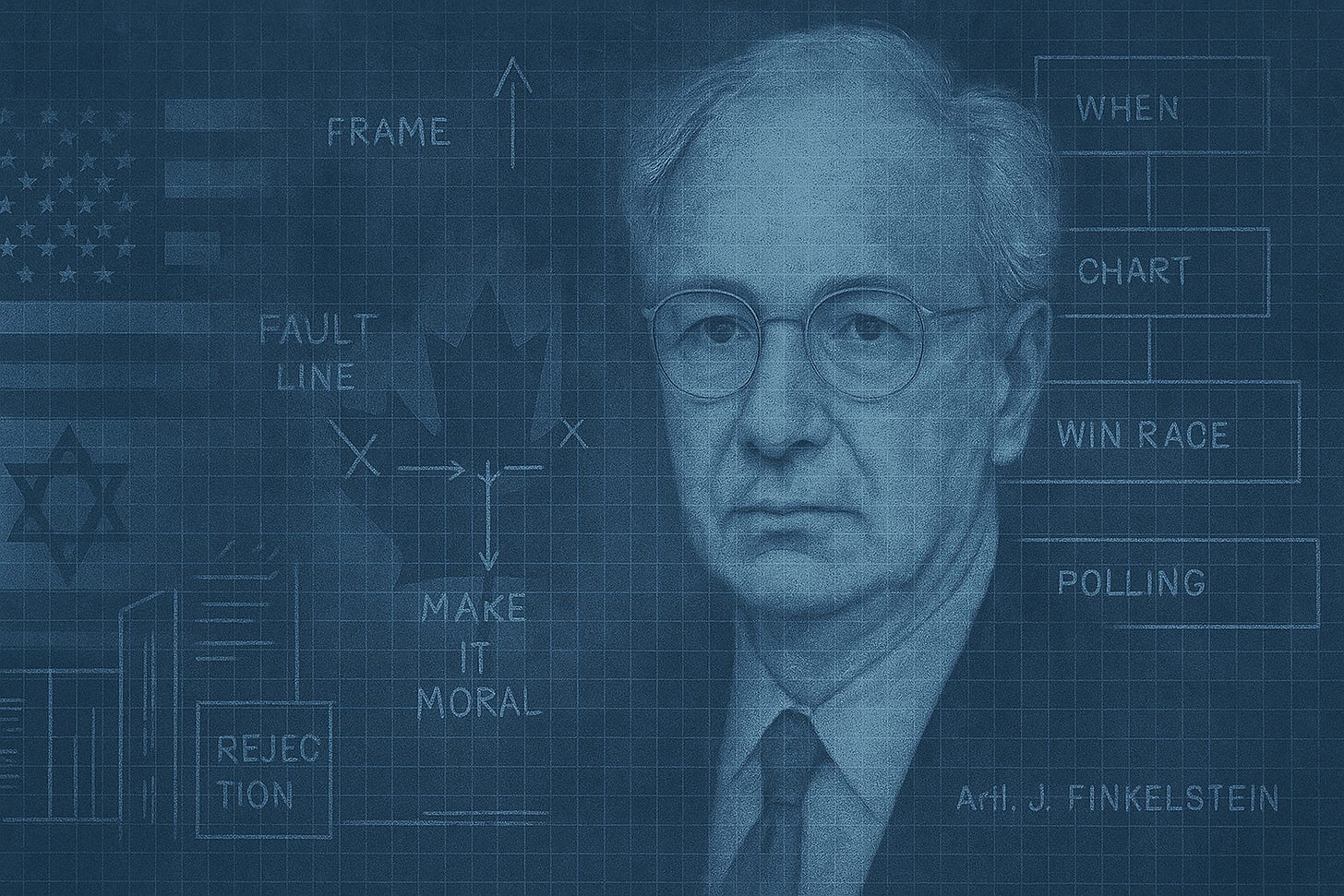

It’s the ghost in the machine: Arthur J. Finkelstein — an American polling savant whose minimalist, negative, relentlessly repetitive style migrated from New York and Washington to Jerusalem and, eventually, Ottawa.

He helped teach a generation of centre-right leaders to win by making voters say no to the other side. That method — born in U.S. Senate races, sharpened in Israel with Likud, and adopted in Canada during the Reform-Alliance realignment — still animates the CPC’s political reflexes 1 2.

How the right cracked and re-formed

The Progressive Conservative Party suffered one of the most dramatic collapses in modern democratic politics following Mulroney’s exit from politics: from majority government to just two seats in 1993.

That shock clarified one thing — if the Canadian right wanted to govern again, it needed a new offer and a modern campaign toolkit.

Cue the Reform Party’s rise, the Canadian Alliance under Stockwell Day, and finally the 2003 merger with the PCs that created today’s Conservative Party of Canada under Stephen Harper.

The design of that merger — equal parts messaging and machinery — paved the way for a foreign operating system to take root inside a Canadian institution. 3.

Who was Arthur Finkelstein?

Arthur J. Finkelstein was the most influential political consultant you’d likely never heard of. In the 1970s and 1980s, he cut his teeth on hard-edged Republican campaigns — Al D’Amato’s Senate run in New York, Jesse Helms’s culture-war battles in North Carolina, George Pataki’s gubernatorial rise — and built a reputation for precision attack politics.

A committed conservative, he believed elections were won not by persuasion but by definition. His signature was a spare, brutal vocabulary: liberal, liberal, liberal. The word became his scalpel, wielded to make moderation sound suspect and progressivism sound dangerous — repeated through ten-second ads and talk-radio riffs until it branded an entire ideology as the enemy. 4.

In 1996, TIME magazine called it “Finkel-think”: a shorthand for negative, repetitive labeling that shifts voters into what he called rejectionist voting — don’t choose who you love; vote against who you’ve learned to fear 5.

By the 1990s he was running the National Republican Senatorial Committee’s strategy shop and exporting his craft. His personal papers, now at the Library of Congress, document work not only across U.S. races but also with Canada’s National Citizens’ Coalition and Israel’s Likud 6.

The method arrives in Jerusalem

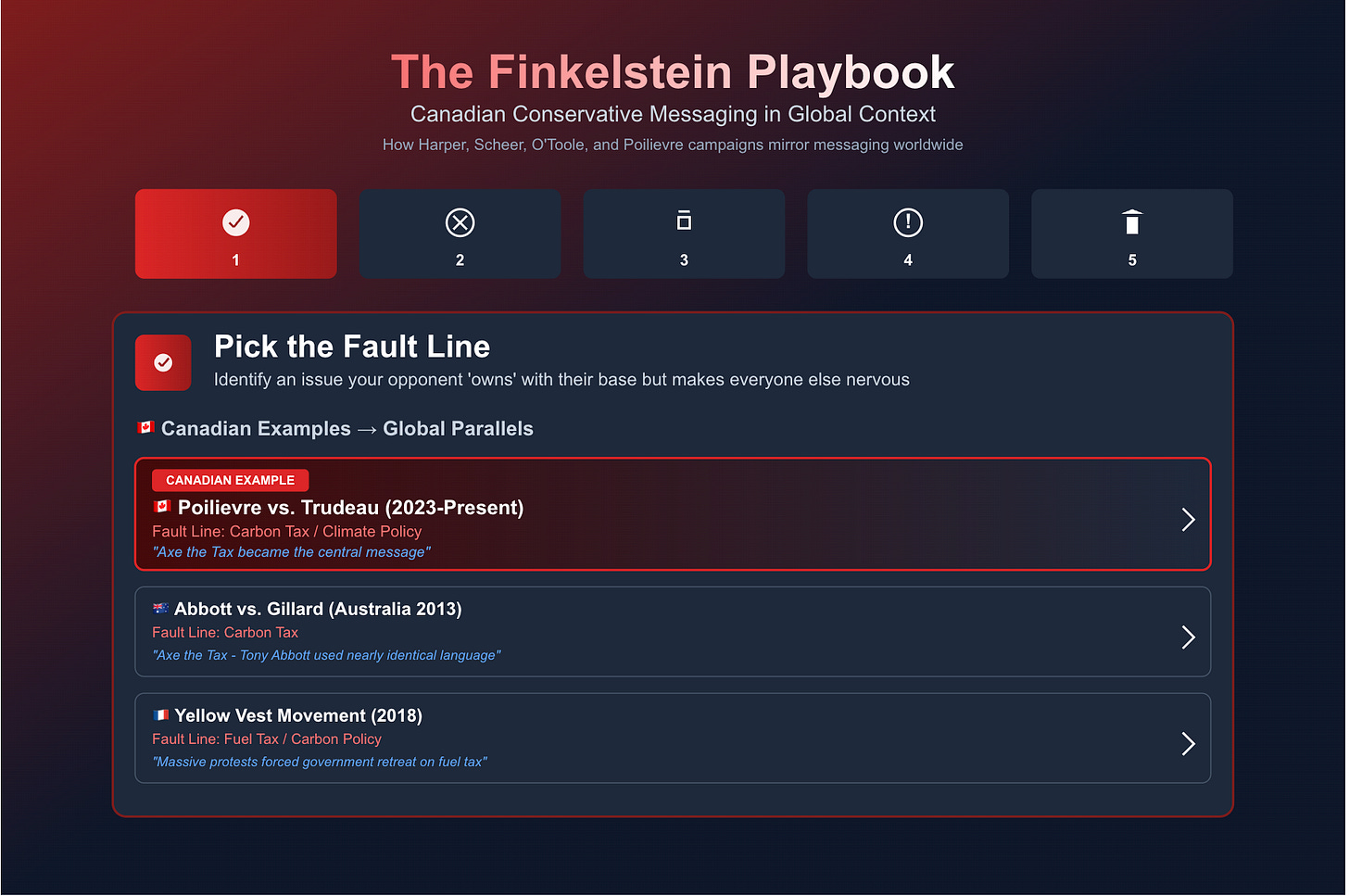

If there’s a single campaign that shows the blueprint in full, it’s Israel’s 1996 election, when Benjamin Netanyahu eked out an upset over Shimon Peres.

Finkelstein’s polling zeroed in on one emotionally loaded fault line — Jerusalem — the ultimate symbol of sovereignty and identity in Israeli politics.

His data showed that fear of dividing the city could override every other policy concern. The campaign built around that insight was ruthless in its simplicity, repeating a four-word cudgel: “Peres will divide Jerusalem.”

The message bypassed debate and went straight to instinct — fear, belonging, betrayal — making it instantly legible to low-information voters and deeply polarizing to everyone else.

It reframed the entire election around a single, existential question, turning nuance into liability and emotion into strategy.

The creed — Only we can keep you safe — outlived the campaign that coined it. What began as a promise to guard Jerusalem evolved into a template for modern conservative politics: redefine safety not just as security from threats, but as protection from change itself.

In Israel, it became the backbone of Netanyahu’s long rule; in the United States, it merged seamlessly into post-9/11 rhetoric that cast dissent as danger; and in Canada, it found new life in a politics that equates “safety” with cultural stability, economic order, and resistance to imagined chaos.

The language has changed — crime, borders, inflation, identity — but the structure remains the same: a binary moral frame that divides the world into guardians and threats. That was Finkelstein’s lasting gift to the modern right — a politics that sells fear as security, and belonging as defense.

That Likud victory became the hinge in our story: the playbook that won in Israel is the same one that later synced — through networks and personnel — with the project of reconstructing Canada’s right.

Netanyahu would reuse that framing for decades. Its moral contrast — protector versus reckless — became Finkelstein’s signature.

From Reform and Alliance to Harper: Canada installs the operating system

In the early 2000s, as the Reform and Alliance movements merged with the Progressive Conservatives, Stephen Harper was steeped in message discipline and institutional control. His years at the National Citizens’ Coalition had honed a distrust of bureaucracy and a belief in communications as strategy, not support.

When he took over the new Conservative Party, Harper and his inner circle applied a Canadianized version of the Finkelstein method: compress the ask, define the enemy, repeat the frame.

Their message distilled to a similar creed — Only we can keep you safe — though “safety” in this case meant economic order, cultural continuity, and protection from the perceived recklessness of Liberal governments. It was less about fear of physical threat and more about shielding a fragile national identity from disruption.

Every policy and talking point was filtered through that protective lens: security, stability, control. The result was a politics of reassurance wrapped in vigilance — a northern echo of the emotional architecture Finkelstein had built decades earlier.

The 2008 “Not a leader” ads that bracketed Stéphane Dion’s tenure were paradigmatic: short, simple, omnipresent. By 2011, the Conservatives layered a positive-sounding meta-narrative over it — “Strong, stable, majority government.” Both reduced complex politics to a single, repeatable choice: strength versus weakness 8 9.

Harper moves up the ladder — and the method globalizes

After losing power in 2015, Harper didn’t retire — he scaled up. Three years later, he became Chairman of the International Democrat Union (IDU), a global alliance of centre-right parties founded by conservatives like Margaret Thatcher, George H. W. Bush, and Helmut Kohl.

Within months of his appointment, Likud — the Israeli party shaped by Arthur Finkelstein’s playbook — formally joined the network. Today, the IDU’s roster spans the democratic right across continents: Canada’s Conservative Party, the U.S. Republicans, Fidesz in Hungary, and Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS). What began as an informal exchange of strategy has matured into an institutional pipeline linking messaging, money, and personnel across borders.10.

The IDU doesn’t command; it coordinates. It trains staff, shares data techniques, and keeps messaging in sync — a political supply chain of shared tactics moving under different flags.

This is hierarchy blindness in action — the tendency to mistake the absence of visible authority for the absence of structure. Just because power isn’t announced through titles or uniforms doesn’t mean it isn’t operating. In flat or “horizontal” organizations, hierarchies often go underground: influence hides behind consensus, authority flows through personality and proximity, and decisions still move through invisible chains of approval.11.

Why the CPC’s Israel line sounds like Likud

When Canadian Conservatives brand themselves as uniquely pro-Israel, it’s really pro-Likud. Harper’s 2014 Knesset address — “Through fire and water, Canada will stand with you” — echoed Finkelstein’s Israeli rhetoric almost line for line: moralized steadfastness, a binary between loyalty and betrayal 12.

Once you trace the consultant networks and Harper’s post-PM IDU work, the CPC’s alignment with Netanyahu’s Likud stops being mysterious. It’s the same architecture of persuasion: protector versus threat, order versus instability.

From Harper to Poilievre: the algorithmic upgrade

Pierre Poilievre didn’t inherit a manual; he grew up inside the system Harper built. What he added was distribution.

The slogans — “Axe the Tax,” “Gatekeepers,” “Building Homes, Not Bureaucracy” — are pure Finkelstein: one-frame moral contrasts, engineered for repetition. But Poilievre’s innovation lies in the delivery system. His YouTube-first, engagement-maximized strategy doesn’t just broadcast the message — it trains the algorithm to carry it. The feedback loop between outrage, attention, and amplification becomes the campaign itself.

If Harper installed the operating system, Poilievre discovered the growth hack. The ghost hums louder now, tuned to the frequency of the feed. 13 14.

A rare confession from the architect

In a 2011 lecture in Prague, Finkelstein looked back at his career and said:

“I wanted to change the world. I did. I made it worse.” 15

—Arthur J. Finkelstein

It was the closest he ever came to regret — not over a single campaign, but over the architecture of influence he’d helped design.

By then, his language had outlived him, embedded in the code of politics itself. His disciples didn’t need his supervision; they were fluent in the method. And like many of them, Finkelstein never stopped using it, because it still worked so effectively.

That’s the moral hazard at the heart of modern conservative communication: the method’s success became its justification. Winning came first; reflection could wait.

The moral: addiction, fatigue, renewal

And that’s the risk of living by wedges: fatigue. People can absorb only so much moral emergency before they tune out — even your own supporters.

The method that rescued the right after 1993 and powered its modern rise is the same method that now traps it in a cycle of diminishing returns. The constant need for an “enemy” makes it harder to build a durable majority.

Finkelstein knew what his craft could do to a society — make it distrustful, divided, perpetually on edge — and he ran it anyway.

The Conservative Party may do the same.

Or it could choose renewal: treat message discipline as a tool, not a theology. Widen the emotional range beyond anger and certainty. Rediscover the Progressive Conservative instinct to add rather than only exclude.

Ghosts leave when the living change the script.

Sources

Canadian Press. (1993). Election results: Progressive Conservative collapse. CBC Archives. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/archives

Arthur Finkelstein. (2025). Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Finkelstein

Malloy, J. (2016). The Conservative merger and the evolution of party communication in Canada. Journal of Canadian Studies. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcs.2016.34

TIME Magazine. (1996). The Power of Negative Thinking. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,984596,00.html

Pataki, G. (2014). Interview: Campaign reflections on 1994 race. New York Historical Review. https://nyhistoryreview.org/pataki-1994

Library of Congress. (2022). Arthur J. Finkelstein Papers, Finding Aid. https://findingaids.loc.gov/ead3pdf/mss/2022/ms022002.pdf

Miller, M. (1996, February 19). Likud salvo accuses Peres of wanting to divide Jerusalem. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1996-02-19-mn-37720-story.html

Flanagan, T. (2013). Winning Power: Canadian Campaigning in the 21st Century. University of Toronto Press.

Cross, W. (2015). Permanent Campaigning in Canada. UBC Press.

International Democrat Union. (2018). Stephen Harper elected Chairman of the IDU. https://www.idu.org/harper-elected-chairman

Northern Variables. (2024). The Quiet Network: Keiretsu Politics. https://northernvariables.substack.com/p/the-quiet-network

Harper, S. (2014). Address to the Knesset. Government of Canada Transcripts. https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/news/speeches/2014/01/20/address-knesset

Northern Variables. (2024). Views, Rage, Repeat: How the Conservative Party Became a Media Powerhouse. https://northernvariables.substack.com/p/views-rage-repeat

YouTube Data Tools. (2023). Pierre Poilievre Engagement Metrics. https://data.youtube.com

Finkelstein, A. (2011). Lecture at CEVRO Institute, Prague (Video). https://www.cevro.cz/en/article/finkelstein-lecture-2011