Loving Canada Means Understanding How Our Democracy Actually Works

Why floor crossing, minority governments, and parliamentary weirdness are signs of a healthy system—not a broken one

There is a strange reflex in Canadian politics right now. It shows up whenever something unfamiliar or a little untidy happens inside our parliamentary system. Someone almost always rushes in to declare it undemocratic. Some of that comes from a genuine rise in political interest, which is not a bad thing. But that interest is often shaped through partisan channels, producing outrage without the procedural grounding needed to understand what is actually going on.

An MP crosses the floor. Undemocratic.

A government governs without a majority. Undemocratic.

A government survives confidence vote after confidence vote. Illegitimate.

A party leader loses control of their caucus. Chaos.

Much of this confusion is not accidental. It has been cultivated by years of permanent campaigning, where opposition parties treat Parliament less as a place to govern and more as a place to force collapse. The result is scandal inflation. Ordinary parliamentary friction is recast as crisis. Routine governance is framed as illegitimacy. Every vote becomes a potential confidence trigger. Procedural tools are used for maximum disruption, and bringing down the government becomes an objective in itself rather than something that follows from presenting a credible alternative capable of commanding the House. Over time, people come to expect that minority governments are supposed to fall at the first opportunity.

But that is not how confidence works1.

The System Isn’t Broken. The Expectations Are.

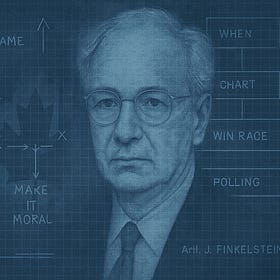

This shift also has a source. Over the past two decades, Canadian politics has steadily imported American-style permanent campaigning tactics that were designed for a very different system. The Conservative Party of Canada, in particular, embraced U.S.-influenced strategies associated with figures like Arthur Finkelstein, where perpetual opposition, grievance-driven messaging, and constant pressure to delegitimize governing institutions are rewarded. These techniques work well in a presidential system with fixed terms and little expectation of legislative cooperation. Transplanted into a Westminster parliament, they quietly distort how confidence, compromise, and minority governance are meant to function.

The Republican Ghost of the Conservative Party of Canada

Prologue: Once you see the wiring, you can’t unsee it

Canada does not have a broken version of American democracy. We have a different one, arguably a better one. On purpose.

Much of the current outrage comes from judging our system against the wrong model. When Parliament does not behave like a presidential system, when governments do not rise and fall on single votes, or when power is dispersed rather than concentrated, it is treated as dysfunction rather than design.

One of the most patriotic things a Canadian can do right now is understand how that system actually works.

Because once you do, a lot of the outrage evaporates.

Parliament Was Built Around People, Not Parties

The most important thing Canadians often forget is this: We elect Members of Parliament, not political parties.

On election day, voters choose an individual candidate in a riding. The party label on the ballot matters politically, but it does not bind the seat legally. Once elected and sworn in, an MP’s authority flows from the electorate and the Crown, not from the party they ran under.

This distinction is not rhetorical. It is constitutional.

In Canadian constitutional law, Parliament, the House of Commons, the Senate, the Crown, the courts, and elected members themselves are constitutionally entrenched institutions. Their authority and existence are recognized by the Constitution Acts.

Political parties are not.

Political parties do not appear in the Constitution Act, 1867 or the Constitution Act, 1982 as rights-bearing constitutional institutions2. They exist in ordinary statute, primarily the Canada Elections Act, for limited administrative purposes such as registration, financing, and ballot identification. Constitutionally, they remain voluntary political associations.

This has a direct legal consequence that many Canadians find surprising. A political party cannot reclaim a seat.

Once an MP is elected, there is no constitutional or statutory mechanism allowing a party to force their removal from Parliament, trigger a by-election, or revoke their mandate. Doing so would require parties to have constitutional standing over parliamentary representation. They do not.

Expelled From Caucus Is Not Expelled From Parliament

Canadian practice makes this distinction unmistakably clear.

Parties can expel MPs from caucus.

They cannot expel MPs from Parliament.

This has happened repeatedly in Canadian history. MPs removed from caucus for ethics breaches, dissent, or loss of confidence by party leadership do not lose their seats. They sit as independents, retain full voting rights, and continue to represent their ridings.

This is not a loophole. It is the system working exactly as designed.

Caucus membership is conditional. Parliamentary membership is not.

Only the House of Commons itself has disciplinary authority over its members, including historically the power of expulsion3. That power belongs to Parliament as an institution, not to political parties.

Floor crossing is simply the inverse scenario. Instead of being expelled from a caucus, an MP voluntarily joins another one. In both cases, the seat remains with the MP, because constitutionally, it must.

Parliament Existed Long Before Parties Ever Did

Many people assume political parties arrived fully formed from the United Kingdom, embedded in the Westminster system from the start.

They did not.

The British Parliament existed for centuries before modern political parties emerged4. Early parliaments were made up of loose factions, regional blocs, personal alliances, and shifting loyalties. Voting was fluid. Coalitions formed and collapsed regularly.

Political parties developed gradually in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as a response to scale, industrialization, and the need for more predictable governance. They were tools to manage Parliament, not constitutional foundations.

Canada inherited this structure. Parliament came first. Parties came later. And they were never elevated to constitutional status.

That historical order still matters.

What the Party Whip Actually Is

The party whip is one of the most misunderstood roles in Canadian politics.

A whip does not possess legal or constitutional authority. They cannot compel votes by law. They cannot remove an MP from Parliament. They cannot force a resignation.

What they do control is political leverage.

Whips organize votes, assign committee positions, manage speaking opportunities, and enforce caucus expectations. Most importantly, parties exert discipline through nomination control.

If an MP wants to run again with a party’s name on the ballot, their nomination papers must be endorsed by the party leader or a delegated official. Without that endorsement, the party label does not appear. In a system where party branding matters to voters, this is a powerful deterrent.

This is why party discipline in Canada is strong, even though it is not legally enforceable. MPs comply not because they must, but because the political consequences of defiance are real.

When an MP defies the whip or crosses the floor, they are not violating democratic rules. They are accepting political consequences.

Sidebar: What MPs Swear Allegiance To (and What They Don’t)

Before a Member of Parliament can sit or vote in the House of Commons, they must swear or affirm an oath required by Section 128 of the Constitution Act, 18675.

“I, <name>, do swear that I will be faithful and bear true Allegiance to His Majesty King Charles the Third.”

That is the entire oath.

There is no oath to a political party.

There is no oath to a party leader.

There is no oath to a platform or campaign promise.

There is no oath to caucus discipline.In Canadian constitutional practice, allegiance to the Crown means allegiance to the state, the Constitution, and Parliament itself. The Crown functions as the legal embodiment of Canada’s democratic authority and continuity.

An MP who crosses the floor does not violate their oath. An MP expelled from caucus does not lose legitimacy. Their constitutional duty never ran to a party in the first place.

If parties were meant to own seats, they would appear in the oath.

They do not.

Party Platforms Are Promises, Not Legal Mandates

Another common misunderstanding is the belief that party platforms are binding commitments.

They are not.

There is no legal mechanism that allows voters to enforce party platforms in court the way a contract would be enforced. Accountability in Canada is political and electoral, not contractual.

The Quiet Network: Keiretsu Politics, the IDU, and Canada’s 45th Election

On the surface, it still feels like Canada and the United States operate in different political realities. Different systems. Different traditions. Different parties.

MPs are representatives, not delegates. They are expected to exercise judgment and respond to changing circumstances. If platforms were legally binding, Parliament would become a rubber stamp for documents written under campaign pressure.

If voters believe an MP or party has broken trust, the remedy is defeat at the next election.

If It Feels Strange, That Does Not Mean It Is Broken

Much of the anger around floor crossing follows the same pattern. Something happens that feels unfamiliar, untidy, or emotionally unsatisfying, and the immediate conclusion is that the system has failed.

But one of the defining features of Canada’s parliamentary democracy is that very little is ad hoc.

Our institutions are old, procedural, and deliberately overbuilt. They are designed around the assumption that people will disagree, change their minds, lose confidence, break ranks, form new alliances, or behave in ways that frustrate simple narratives.

Floor crossing is not an edge case the system forgot to anticipate. It is one of many scenarios that Westminster parliamentary procedure explicitly allows for.

Governments can fall mid-Parliament.

Prime Ministers can be replaced without elections.

MPs can be expelled from caucus and continue to sit.

Minority governments can govern for years.

Confidence can be conditional and negotiated.

All of this can feel counterintuitive if you expect democracy to behave like a contract or a corporate org chart. But these are not accidents. They are features of a system designed to absorb political change without collapsing legitimacy.

Discomfort is not evidence of democratic failure. In many cases, it is evidence that the system is doing exactly what it was designed to do.

Why Understanding This Is Patriotic

When people say floor crossing is undemocratic, what they are really saying is that they believe parties are the true holders of democratic legitimacy.

That belief does not align with Canada’s Constitution, parliamentary history, or legal reality.

Canada’s democracy is built around individuals entrusted with judgment, not brands entrusted with power. It is flexible, deliberative, and resilient. It bends instead of snapping.

Canada does not need to imitate the American system to be legitimate. We do not need presidents, primaries, or rigid party absolutism to be democratic.

We already have a system worth defending.

And learning how it actually works is one of the most Canadian things we can do.

Sources

House of Commons. (2023). House of Commons Procedure and Practice (4th ed.). Government of Canada. https://www.ourcommons.ca/procedure/procedure-and-practice-4/

Elections Canada. (2023). Political parties and candidates. Government of Canada. https://www.elections.ca/content.aspx?section=pol&dir=par&document=index&lang=e

Marleau, R., & Montpetit, C. (2000). House of Commons Procedure and Practice. House of Commons. https://www.ourcommons.ca/marleaumontpetit/DocumentViewer.aspx?DocId=1001&Sec=Ch04

May, T. E. (2023). Erskine May: Parliamentary practice (26th ed.). UK Parliament. https://erskinemay.parliament.uk

Constitution Act, 1867, s. 128 and Fifth Schedule. (1867). Government of Canada. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/section-128.html

Excellent summation of the institution that governs our nation. Always great to be reminded of lessons covered in classrooms often not learnt well enough to be remembered, if at all. Thanks.

Anyone who gets their knickers in a twist about MPs who cross the floor should remember that one of the greatest statesmen and parliamentarians of the 20th century, Winston Churchill, did it. Twice.